China Aid Expert Commentary March 24, 2013

ChinaAid’s 2012 annual report on persecution of churches and Christians in China has sparked an online dialogue, with reactions ranging from support to doubts and even rejection. On Monday Feb. 25, Christianity Today ran two pieces by two experts on the church in China under the headline “China Isn’t Trying to Wipe Out Christianity.”

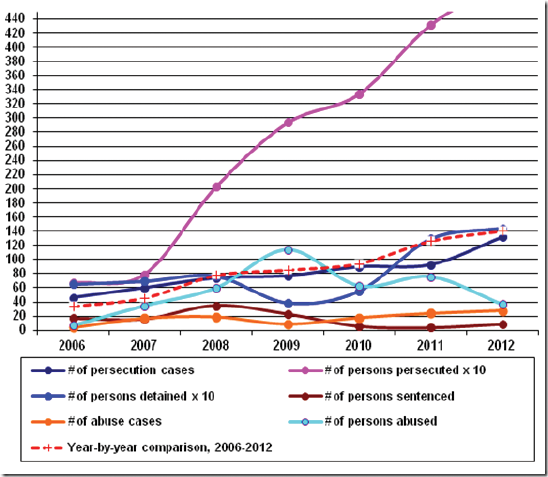

In response, ChinaAid wishes to point out first that those who question and doubt our 2012 annual report appear to have overlooked this key point: “In 2012, Christians and churches in China experienced a serious comprehensive escalation of government persecution. In comparing the total number of persecution cases, the number of people persecuted, the number taken into custody, the number sentenced, the number of abuse cases and the number of people abused with the same figures for 2011, the total of all six categories rose 13.1% over the previous year…” The report also lists “the Main Characteristics of and Reason Behind 2012 Persecution: To Eradicate House Churches.”

The following chart from ChinaAid 2012 Persecution Report in China shows the escalation of the persecution in the past 7 years in a row. (Read all 7 years’ reports here: https://chinaaid.org/chinaaid-annual-reports/)

The first CT piece, “China’s Actions Are Not About Christianity,” was written by Brent Fulton, president of ChinaSource and the editor of ChinaSource Quarterly. His basic point was, “On their face these numbers appear to be cause for serious alarm, and the China Aid report has in fact spawned headlines decrying the beginning of the end of the house church in China. However, upon closer examination these statistics do not support China Aid’s assertion of a nationwide government-sponsored campaign against Christianity in China.

The problem here is three-fold. First, the problem of persecution is indeed serious, and ChinaAid’s Christian position is that the persecution of any church, not to mention that of thousands of Christians and their families, should always be considered serious. Incidentally, as Mr. Fulton correctly noted, it was news reports about our report that were “decrying the beginning of the end of the house church in China.” We wish to emphasize that it is not ChinaAid’s belief that this is “the beginning of the end of the house church in China” because we simply do not think that the Communist’s state machinery can ever succeed in eradicating China’s house churches: house churches have grown and spread to such an extent that no group is strong enough to contend with it. Just as happened with the persecution of the early Roman Church as well as the Communist Party’s persecution of the church in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, Chinese government persecution will also fail. Second, the conclusions in our report are supported by our investigations and data, and they show that the persecution in 2011 and into 2012 has been characterized by thorough investigations of house churches and eradication of those churches for which the government has set up files; this is all part of Phases 1 & 2 of the government’s ten-year plan to eradicate house churches. Third, the cases cited in the annual report come from all over China and are just the tip of the iceberg, but they have representative value. Mr. Fulton notes that “the China Aid report mentions only two cases involving Beijing house churches for the entire year.” But if he thinks that the two persecution cases we listed for Beijing were the only two cases of persecution in the Chinese capital in all of 2012, he clearly does not understand the persecution situation that Beijing house churches face. It’s hard to imagine that anyone with a basic understanding of China’s house churches would think that only two cases of house church persecution occurred in Beijing for the whole of 2012.

Furthermore, Mr. Fulton mentions that Christians in China face many “obstacles,” a very imprecise term. He follows up by explaining that what he means is that Chinese Christians do not experience persecution simply for being Christians and house churches do not face persecution simply because they are house churches. Even though his language here is evasive and not forthcoming, his meaning is clear: Chinese churches and Christians are not being persecuted for their faith. China’s house churches hear this kind of thing all the time from government spokespersons and it has long ceased to be a surprise. Mr. Fulton follows with a list of about seven reasons for church persecution, all in an effort to show that these kinds of persecution are not directly linked to faith. The last of the reasons given is that in minority areas, Christianity is viewed as a threat by the dominant religion, but he does not say whether this persecution is from the government or society.

Also, Beijing Shouwang Church is a house church that has been exemplary in doing the utmost to abide by government regulations, but its attempts to follow the government’s requirements to register were foiled by the government itself, which refused for two years to consider Shouwang’s registration application and, in the meantime, terminated its lease arrangements for meeting space, and when Shouwang purchased and paid in full for its own property, the government told the sellers not to hand over the keys to the office building space. The government pressure made it impossible for Shouwang to meet indoors, so it moved its services outdoors in April 2011. Since then, believers are detained every single Sunday when they meet together, with the detentions now totaling hundreds, while Shouwang’s church leaders including its senior pastor and all the elders have been held under extra-judicial house arrest for the past two years. But according to Mr. Fulton’s “triggers that prompt authorities in China to take action against Christian activities,” this situation does not constitute religious persecution because Shouwang’s actions were too provocative and were “bound to provoke a response” from the government.

Consider too the case in Inner Mongolia of a group of house church believers and medical professionals led by pastor Jin Yongsheng who were providing basic medical services such as taking the pulse and blood pressure readings of local farmers and sharing the Gospel with them. For this, they were detained, beaten up and held under administrative detention for days. According to Mr. Fulton, they should not be considered as having been persecuted for their “religious faith” because their activities had “triggered” the Chinese authorities to perceive these church people as a “security threat” for having publicly shared their faith.

And what of the Christian women who, out of their religious convictions, refuse to abort their babies when they get pregnant without government permission and are instead forcibly aborted by family planning officials? One such woman refused to abort her seven-month-old unborn baby and lost her freedom until an international outcry helped free her and save her baby’s life. But by the same logic mentioned above, this situation also does not fall into the category of religious persecution because these women were in violation of China’s one-child policy.

Can we apply the same standard to similar situations in free countries without reaching a different conclusion? Unless there’s a double standard here, all these cases should–according to widely acknowledged international human rights standards–be regarded as Christians being persecuted because of their faith and religious convictions. Even Article 36 of China’s own constitution states that the religious freedom of Chinese citizens is supposed to be protected. Have we lowered the standard by buying into the Communist regime’s interpretation of that clause?

If we were to accept Mr. Fulton’s position, then North Korea could execute Christians not because they are Christians but because their faith and religious practices are political. When Germany was under Nazi rule and Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Niemöller opposed the Nazi persecution of the Jews, this also went against Nazi politics. And the reason for the persecution of the Christians during the Cultural Revolution also was because their faith was politically offensive, so they were labeled “counter-revolutionaries.” To the many Christians who have been persecuted for their faith, espousing this kind of logic is to stand on the side of the persecutors and is simply cruel. Finally, Mr. Fulton admits that China’s policy on religion is “broken” and that “tensions” exist. But what exactly is China’s policy on religion? Consider what sociologist Yang Fenggang says in Chapter 4 of his book Religion in China: Survival and Revival under Communist Rule: China’s current “policy and regulations on religion continue to be guided by ideology, with no substantive change from the situation before the Cultural Revolution. … If these restrictive regulations continue to exist to suppress and attack, then it will be no surprise if the policy on religion becomes the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

As for the other article, by Jan Vermer, it was so vague and so ingratiating that it is not even worth commenting on. If the title “Intensity of Persecution of Christians in China Decreasing, but still a Concern” is the main point of his piece–that the intensity of persecution of Christians is decreasing–this is an argument that’s easy to refute. Mr. Vermer, who works with Open Doors International, cites the organization’s own index of 50 countries where Christian persecution is the worst, pointing out that China in the past decade China has fallen from the top 10 and is now ranked at 37th. If the simple fact that China’s ranking in some international lists of the worst countries for religious freedom has dropped means that religious persecution has improved; it could simply be that religious freedom has gotten worse in other countries, that would be a possible reason. Yet it seems he tried to prove the persecution level in China has decrease which is wrong. These rankings have no bearing at all on ChinaAid’s report and its evidence that persecution in 2012 was more serious than in 2011. In the past decade, due to the extreme leftist ideology of the Hu Jintao-Wen Jiabao government, China experienced serious setbacks in the areas of civil rights, the rule of law, etc. Not only is this widely acknowledged both in China and internationally, it is common knowledge that requires no expert opinion or commentary. The escalation of Christian persecution is just one aspect of the general trend, and is not an exception to the rule. Anyone who believed that the intensity of Christian persecution was decreasing before the experiences of Shouwang Church could be considered to have simply been naive, but anyone who still holds that view now is someone who can’t differentiate between black and white, or even someone who calls black white and white black.

Christian scholars should seek truth in their academic pursuits and speak the truth based on reality and the facts, and they should be compassionate toward the Christian persecuted, as with an injured part of one’s own body. With regard to the issue of the church in China and Chinese politics, diligent study is required so as to improve one’s own understanding and broaden one’s perspective. The work by house church scholar Mark Shan “Beware of Patriotic Heresy in the Church in China” is worth consulting for its profound analysis of the Chinese church and China’s religious policy and for its warning not to repeat the errors of the World War II-era German Christians in Nazi Germany, who—whether wittingly or unwittingly—stood on the side of supporting or whitewashing the persecution of the Jews.

China Aid Contacts

Rachel Ritchie, English Media Director

Cell: (432) 553-1080 | Office: 1+ (888) 889-7757 | Other: (432) 689-6985

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.chinaaid.org