Sunday 24 January 2016 21.22 EST

■ ‘They must be torturing her,’ says Zhao’s mother as she desperately searches for the daughter who vanished seven months ago

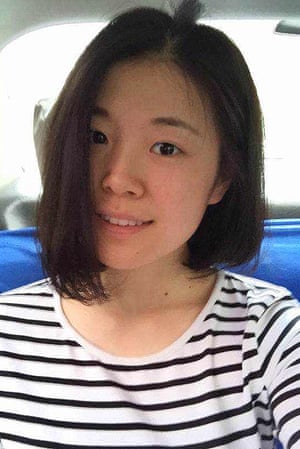

It was a warm summer’s day when Zhao Wei, a 23-year-old legal assistant, kissed her parents goodbye and set out in search of her dreams.

She left her small-town home in central China and headed east to the train station past a Communist party propaganda poster in which president Xi Jinping posed beside the slogan: “If the people have faith … the country will be strong”.

|

| Zhao Wei, a legal assistant, has been detained in the recent crackdown on human rights lawyers in China. Photograph: Adam Dean for the Guardian. |

From there Zhao caught a bullet train to the Chinese capital where she planned to sit the national bar exam she hoped would pave the way for her to become a top human rights lawyer.

“She looked well,” her tearful mother, Zheng Ruixia, recalls of their final moments together, in May last year. “She was so happy when she got on that train.”

Seven months later the would-be lawyer’s dreams are in tatters.

Zhao Wei – who relatives and friends describe as a bubbly and kind-hearted young woman – is behind bars facing trial on political subversion charges that could see her jailed for the rest of her life.

And each day her grief-stricken mother sinks into her daughter’s unmade bed, her hands trembling and tears streaking her face as she leafs through family photo albums chronicling happier times.

“Every day I cry,” says Zheng, 61, sobbing as she reflects on the misfortune president Xi’s rise to power has unleashed on her family. “I just lie on this bed and I cry.”

The story of China’s dramatic lurch back towards repressive dictatorship under Xi is often told on the macro-level: the tale of an unexpectedly authoritarian leader’s do-or-die struggle to preserve the Communist party’s near seven-decade reign by stifling any and all dissent.

But at the ground level, the story is not one of political ideology or the corridors of power but of empty bedrooms and broken homes created by Xi’s intensifying assault on anyone his regime deems a threat.

Since he became the Communist party’s general secretary, in November 2012, Xi’s dragnet has sucked in activists, bloggers, journalists, lawyers and liberal academics.

Now, Zhao Wei – a fan of slushy Korean soap operas and online chat groups, whose gentle manner earned her the nickname “Koala” – has found herself in the crosshairs.

|

| Zheng Ruixia, mother of Zhao Wei, who has been detained since 10 July 2015 in the recent crackdown on human rights lawyers in China. Photograph: Adam Dean for the Guardian |

Born in 1991, the second of two children, Zhao was raised in a middle-class home in Jiyuan, a small city about 740km southwest of Beijing, in Henan, one of China’s most deprived regions.

Growing up, “Weiwei” was a vivacious and outgoing tomboy who expressed a desire to help the less fortunate, her mother says. “She is someone who hates injustice like poison. Even as a child she was like this.”

That idealism initially drew Zhao towards a career in reporting. In 2009, aged 18, she left home to study journalism at Jiangxi Normal University in the eastern city of Nanchang.

She threw herself into social work and campaigned on issues including LGBT rights and HIV awareness. “She saw so much inequality in society,” her mother remembers. “She wanted to help the vulnerable.”

As Zhao entered her final year – and a biting political chill set in with Xi’s elevation to commander-in-chief – Zheng cautioned her daughter against becoming too involved in activism. “I told her, ‘You are very young still.’”

But Zhao was unmoved. “I am here to change society, not to get used to it,” she replied.

At the same time she was showing a growing interest in the work of China’s “weiquan” or “rights defense” attorneys – a community of outspoken activist-lawyers famed for daring to take on politically sensitive cases that often brought them into conflict with the government.

She decided she would try to join their ranks.

|

| Zhao Wei, who is facing political subversion charges in China after falling victim to president Xi Jinping’s crackdown on dissent |

In August 2014, having graduated from university and spent a year working for a website in south-east China, Zhao moved to Beijing and quickly found work withLi Heping, a respected Christian lawyer known for defending dissidents, persecuted religious groups and environmental activists.

At the time Zhao could not have known it but when, on 8 October 2014, she started work at Li’s Beijing law practice, she placed herself at the eye of a rapidly intensifying storm that would soon pulverise her ambitions to follow in her employer’s illustrious footsteps.

The perverse genius of terror is what we are witnessing

Terry Halliday

Just over nine months later, on 10 July 2015, as an unprecedented government crackdown was launched against Li and his fellow human rights lawyers and dozens were hauled off into custody, 10 unidentified men would appear at Zhao’s front door in Beijing.

After ransacking her home, they spirited the young legal assistant off into secret detention. Zhao has not been seen since.

Beijing has used state media to defend its roundup of the supposedly “rabble-rousing” human rights lawyers as well as the decision to hold Zhao Wei.

In a recent editorial the party-controlled Global Times argued: “[T]here is no logic that this young lady … definitely has not committed actions that harm national security. A few people are trying to instigate public opinion by stressing her ‘innocence’.”

Some of those in custody had received “special attention from overseas forces”, the newspaper alleged.

But the ferocity with which Xi’s Communist party has decided to pursue and punish those at the centre of its crackdown has shocked activists, diplomats and veteran observers of China.

Many say they are surprised at the pace at which Xi’s China now appears to be sliding back towards a far more unforgiving form of authoritarianism than has been seen in recent years.

“The perverse genius of terror is what we are witnessing,” says Terry Halliday, an American Bar Foundation scholar who studies China’s human rights lawyer community and knows several of those detained, including Zhao Wei’s boss, Li Heping.

“Essentially, the party hierarchy has just taken off the gloves. It is no longer exercising power through velvet gloves. It has now got knuckledusters on.”

Word that Zhao had fallen victim to what activists call Xi’s “war on law” reached her mother by way of a telephone call from a friend at about 11pm on 10 July.

Earlier that day Zhao had failed to reply to a video her mother had sent her over WeChat, the social messaging service, showing her four-year-old niece dancing on a bed. Zheng assumed she had been busy swotting up for her exam and thought little of it.

In fact the plainclothes officers had already knocked on Zhao’s door and she was in secret detention. When her two flatmates returned to the property they found it had been turned upside down. Papers, documents and clothes were strewn all over the floor.

For the next six months, Zhao’s parents heard nothing. A group of human rights lawyers set off on a fruitless quest for information, visiting detention centres and police stations in northern China where they believed the missing lawyers – and Zhao – might be being held.

By 19 October, the day before her daughter’s 24th birthday, Zheng was so desperate for news that she boarded a train for Tianjin, a city to the east of Beijing, where the lawyers suspected Zhao was in custody.

With her she took a bag of winter clothes and the faint hope that she would be allowed to spend just a few brief moments with her daughter.

But police officers turned her away. “I felt so cold,” Zheng wrote of the experience in open letter that was published on the internet in an attempt to draw attention to her daughter’s case. “I cried so much.”

Deprived of answers, Zheng now has nightmares about her daughter’s plight.

|

| Zheng Ruixia on her daughter’s bed where she spends most of her days, at her home in Jiyuan, China. Photograph: Adam Dean for the Guardian |

“I think they must be torturing her,” she says, clenching a wad of tissues in her fist as she battles to hold back the tears. “Why won’t they let me see her? They must be torturing her. I suspect she is badly injured. That is why they don’t want me to see her. Otherwise what possible reason could they have for forbidding us from seeing her for six months?”

The government has broken the law. I feel helplessZheng Ruixia

With the arrival of the new year, Zheng felt renewed optimism that her daughter might soon be freed, following an initial six-month period of detention after which prisoners must be released or charged.

But on 11 January at 5.30pm those hopes were crushed when a postman arrived at the door of the family home in Jiyuan bearing an official arrest notice from public security authorities.

“My heart was pounding when I saw it,” Zheng remembers. “I was hoping for and expecting good news. But when I opened the letter …”

Inside the envelope was a terse, boilerplate statement from authorities addressed to Zhao’s 61-year-old father, Zhao Yonghong.

“With the approval of the Number Two Branch of the Tianjin Municipal People’s Procuratorate, our bureau arrested Zhao Wei at 6pm on 8 January on suspicion of the subversion of state power,” it read. “She is now being held in custody at the Tianjin No.1 detention centre.”

Zheng says she has hidden the severity of that charge – which potentially carries a life sentence – from her husband who was left badly debilitated by a series of strokes before his daughter’s detention and speaks with a slur.

So as not to weep in front of him, Zheng now sleeps in her daughter’s empty bedroom beneath a black-and-white portrait of their absent child. “I’m afraid that if he knows all the details he will get worse,” she explains.

|

| Zhao Wei, who is facing political subversion charges in China after falling victim to president Xi Jinping’s crackdown on dissent. |

Zhao was a firm believer in ideas such as democracy, freedom and justice, her mother says, but she rejects the implication that her daughter had been conspiring to destabilise the government.

“She did not do it for sure. Zhao Wei loved this country,” she says, adding: “The government has broken the law. I feel helpless.”

Halliday said he believed the Communist party’s decision to target not only prominent human rights lawyers but also their young staff was designed to induce fear in anyone considering opposing its rule.

That it was destroying a young woman’s life and dreams in the process, “is not, of course, lost on the regime,” Halliday added. “I am sure it is part of the calculus of terror.”

That calculus has taken a devastating toll on Zhao Wei’s family.

“The past week has been so hard. I can’t sleep. I can’t eat,” her mother sobs, as she sits alone in the family’s dimly lit sitting room. “We want to appeal but I don’t know who to appeal to.”

“The Communist party is in charge. Whether you have committed a crime or not all depends on what the Communist party decides,” she says.

“Even if you didn’t commit a crime, if [the party] says you did, then you did. End of story.”

Additional reporting by Christy Yao

China Aid Media Team

Cell: (432) 553-1080 | Office: 1+ (888) 889-7757 | Other: (432) 689-6985

Email: [email protected]

For more information, click here