The Guardian

By Tom Phillips in Beijing

Tuesday 7 June 2016 21.58 EDT

■ Li Heping’s six-year-old daughter Li Jiamei dresses as a superhero, hoping to free her human rights lawyer father from prison

With a superhero’s green and blue cape cascading down her back, Li Jiamei skipped into her Beijing nursery wielding a pink plastic sword.

When classmates asked the Chinese schoolgirl who she had come to the Halloween fancy dress party as, she had an immediate reply.

|

| Li Jiamei, the six-year-old daughter of Li Heping, has not heard from her father since he disappeared in July 2015. |

“I want to be a knight!” Li declared. “That way I can rescue my dad!”

For all her gallantry, it is a battle the six-year-old is unlikely to win.

Li Jiamei is the daughter of Li Heping, a top Chinese human rights lawyer who has not been heard of since he disappeared into the custody of China’s security services in July 2015.

Next month will mark one year since China beganan unprecedented attack on such lawyers, rounding up and interrogating more than 300 people in what activists believe was a bid to cow the country’s vibrant “rights defence” movement and strike a blow to those daring to challenge the administration of President Xi Jinping.

Nearly 12 months after the crackdown began, human rights groups say at least 20 of its targets remain in detention facing accusations that they connived to overthrow China’s authoritarian one-party system. Li Jiamei is still waiting for her father to come home.

“She’s small. She misses her dad,” said her mother, Wang Qiaoling, during a two-hour interview conducted in the smokey backroom of a Beijing café in order escape the gaze of security agents who now monitor the lawyers’ families around the clock. “I tell her I miss him too and that we must try to get through this together.”

Deprived of all contact with her husband for almost a year, Wang, who is a devout Christian, looks to the Bible for solace.

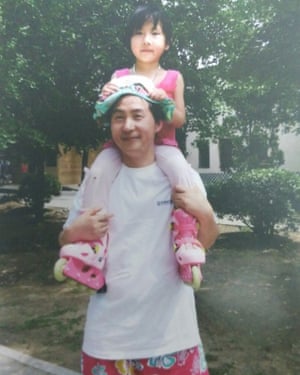

|

| Li Heping pictured with his daughter. Photograph: None |

“We know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose,” said the 44-year-old, quoting from the Epistle to the Romans.

China’s “war on law” began in the early hours of Thursday 9 July last year when a 44-year-old attorney named Wang Yu was taken from her home in Beijing. Just months earlier she had foreseen her detention, telling a friend:“Nobody is safe under a dictatorship.”

Over the following days many of the country’s leading activist-lawyers were seized, including Li Heping, a Beijing-based Christian attorney famed for defending political dissidents such asChen Guangcheng and Gao Zhisheng.

Those bundled into secret detention included not just some of China’s most experienced and outspoken civil rights lawyers but also their young employees, such as Zhao Wei, an idealistic 24-year-old legal assistant who has also been held incommunicado since July.

“All I can say is that I feel furious and helpless,” Zhao’s husband, You Minglei, said this week amid unconfirmed reports that she been physically abused by prison guards. “We still haven’t been given any information [and] in the last few days we’ve heard she was assaulted in the prison. I don’t know what to do.”

Andrew Nathan, a Columbia University expert in Chinese politics and human rights, said the crackdown was part of a wider bid to rein in dissent and reshape Chinese society that has accelerated since the country’s “Napoleonic” president, Xi Jinping, took power in 2012.

“[Lawyers and activists] are just garbage to him. They are not part of his vision of a future China,” Nathan said of those who have fallen victim to the intensifying repression under Xi.

“I think he believes in a future China where everybody accepts their lot, pulls together under the wise leadership of the leadership. His notion of a beautiful future China is not going to be one with a free press or independent media but one with a well-disciplined Communist party that is honest and moral and works for the people and where not everybody’s selfish demands can be satisfied.”

Nathan admitted it was impossible to know whether Xi had issued specific orders for the detentions or whether the repression – which many describe as the worst in nearly three decades – was simply the result of security chiefs reacting to an increasingly hard-line “jingshen” or “spirit” that had gripped China since he became leader.

Either way, he said the harshness of the current campaign reflected Xi’s nervousness as he attempted bold and potentially destabilising reforms of the economy, the military and the Communist party itself, through a ferocious anti-corruption campaign. “It’s sort of as you cross a chasm on a tightrope your muscles tense up.”

Li Jiamei, the youngest of two children, had just started her summer holidays when she became ensnared in the unforgiving world of Chinese politics.

|

| Li Jiamei poses for a portrait with her mother Wang Qiaoling in her bedroom at home in Beijing. Photograph: Adam Dean for the Guardian |

She woke, on the morning of Friday 10 July, intent on spending the day with her dad, her mother recalled. “She begged her father to take her to work. And then it happened – that was the day.”

At about 10am, father and daughter pulled up outside the law firm where he worked on Beijing’s Liangmaqiao Road. Within seconds, Li’s brown Honda SUV had been surrounded by police.

Wang, who has been married to the lawyer for almost two decades, said her husband had refused to be taken without safely delivering the couple’s daughter back home.

After a discussion, the police relented. Two officers raced back to the lawyer’s home in his car, leaving young Li Jiamei with her mother. Li Heping was led away. Months later a 200 yuan (£21) speeding ticket was delivered to their home.

Wang said she initially failed to grasp the severity of her husband’s situation. After all, in more than a decade on the frontline of the fight for human rights, he had been beaten, detained, tortured and abducted and suffered regular harassment from security officials. This time, “I thought they might just have summoned him for a chat,” she said.

In October last year, Li Jiamei posted a birthday message to her absent father on Youtube in a move relatives hoped would draw attention to his plight.

“Daddy. When are you coming back?” the little girl asks in the video. “Come back immediately!”

He did not.

In fact, only in January did Li’s family even discover where he had been imprisoned after an official arrest notice arrived confirming he was being held in Tianjin, a city to the southeast of Beijing, on subversion charges that carry a potential life sentence.

|

| Li Heping has been missing since July 2015 when he was taken from his Beijing home by police. Photograph: Supplied |

Wang, herself a lawyer, rejects the claim her husband and his fellow lawyers were colluding to topple the Communist party as a “farce”. “The entire process has been unlawful from the very start,” she said.

It is a verdict shared by much of the international community.

“Accusations of ‘subversion of state power’ or ‘incitement to subversion’ deny the nature of the work of these human rights defenders,” the European Union said last month in a statement calling for their release.

During a recent congressional hearing on human rights in China, Republican senator Chris Smith accused Xi Jinpingof waging “an extraordinary assault on civil society and advocates for human rights”.

Beijing’s refusal to step back from the crackdown has alarmed western observers and governments who view the deteriorating human rights situation as part of a wider trend of Chinese intransigence under Xi on issues ranging from territorial disputes in the South China Sea to political reform in Hong Kong.

“He doesn’t care if you like him or don’t like him,” Nathan said of China’s leader. “He’s not looking around to see what reaction he gets. He’s just very determined on his goals and I think he believes, like Napoleon, that if I continue on forwards others will yield as I move.”

The clampdown has taken a painful toll on the partners and children of those behind bars, even if many of the youngest struggle to comprehend the political tornado that has sucked up their parents.

With each week, the list of individual tragedies has grown longer.

Yuan Shanshan, the 36-year-old wife of Xie Yanyi, another detained attorney, was one month pregnant when her husband was detained on 12 July 2016.

Xie, who remains in custody, was not there to hold her hand when she gave birth to a baby daughter in March. He was also unable to attend his mother’s funeral after she died on 22 August last year.

Bao Zhuoxuan, the 16-year-old son of Wang Yu and her husband, Bao Longjun, has been robbed of both his parents. He now lives under heavy surveillance with his grandmother in Inner Mongolia having been captured by security agents last October during a foiled attempt to smuggle him into exile in the United States through south-east Asia.

|

| Li Wenzu, 31, wife of imprisoned lawyer Wang Quanzhang poses with their son Wang Guangwei, aged three. Photograph: Adam Dean for the Guardian |

Wang Guangwei, the three-year-old son of Wang Quanzhang, another imprisoned lawyer, has also been deprived of his father. “It has turned our life upside down,” said Li Wenzu, his 31-year-old mother.

Wang Qiaoling, who also has a teenage son with Li Heping, said she had turned to the spouses of other jailed attorneys for support. She makes regular trips around China to visit fellow victims in their hour of need and has staged small demonstrations outside the prison where some lawyers are being held.

“I miss him so much but I have decided to miss him in a happy way,” she said. Wang was herself taken into custody on Monday following her latest protest. “I can miss him and still be happy at the same time. I can be happy in standing up for our rights. And I can also try to make others happy. That is a choice we can make. As for having our families taken away from us, we don’t have any choice about that.”

Nathan said the offensive against government critics and independent thinkers was paying off for the Communist party.

“People get the message. They are shutting up. They are being more careful. And those who have been the most active are struggling with their personal lives – they are either in jail or have lost their job or been fired from their law firm and so forth.”

But the spouses of China’s missing lawyers are refusing to go quietly.

“If someone attacks you, you’re not just going to just stand there and let them beat you, are you?” said Li Wenzu, who has also continued to speak out in defiance of threats from security officials.

Li confessed she had even started to enjoy the thrill of being constantly trailed by government spies and finding ways to shake them off. “Right now, life is colourful,” she said with an uneasy grin.

Li Jiamei has also refused to give up the fight.

Earlier this year, Wang recalls a playmate turning to Li Heping’s chivalrous daughter and asking what she wanted to be when she grew up.

For that question, the six-year-old had an answer too. “I’ve decided I want to be a human rights lawyer,” she said.

Cell: (432) 553-1080 | Office: 1+ (888) 889-7757 | Other: (432) 689-6985

Email: [email protected]

For more information, click here