|

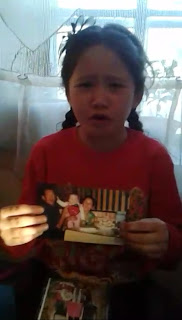

| A child pleads for the release of her father, who has been imprisoned in Xinjiang during a crackdown on ethnic minorities. (Photo: ChinaAid) |

ChinaAid

(Urumqi, Xinjiang—Oct. 17, 2018) As notorious “re-education camps” teem with more than 1 million wrongfully imprisoned ethnic minorities, police in China’s northwestern Xinjiang have been transporting Muslim prisoners to other locales.

On the morning of Sept. 18, Xinyuan County police, located in Xinjiang, dispatched hundreds of special armed officers to relocate about 3,000 people out of an imprisonment center, using more than 50 buses. They implemented comprehensive traffic control, forcing smaller cars to make way for the buses.

“Residents were forbidden from opening their windows and taking pictures,” an anonymous insider said. “Some people’s mobile phones were confiscated.”

Another resident reported that they asked a “re-education camp” administrator where the prisoners were being sent but were told that the destination is unknown.

More than 1 million people have been held in these camps, which torture, starve, and brainwash inmates, who are incarcerated on trumped up charges. China says such measures help curb terrorism among the region’s ethnic minorities, which make up a majority of the local population, but instead, they have led to people being racially profiled and imprisoned for actions as trivial as making plans to travel abroad. In addition, many ethnic minorities born in China who have emigrated to other countries are often lured back into the country, have their passports confiscated, and are locked away.

Muhe Yati Elip’s brother, Ayati Elip, was taken into custody after his niece installed WhatsApp, a social media software, on his phone. Local police quickly summoned Ayati Elip and accused him of using WhatsApp, a social media software. When Muhe Yati Elip became aware of the situation, he went to the local police department to explain. He then returned to Kazakhstan, where he lives, a few days later.

After 10 days, however, the police put Ayati Elip in a “re-education camp,” and Muhe Yati Elip traveled back to China to plead for his freedom, submitting two written explanations to the local police department. However, his brother has not yet been released.

“It has been more than 11 months,” Muhe Yati Elip said. “We have not been able to contact my brother to this day. I don’t know whether he is still alive.”

Likewise, Nuerlandbieke Amaan, a 24 year-old resident of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang, was arrested by the government in July 2017 because the government termed information on his cell phone “sensitive.” He was later sentenced to 10 years in prison and is serving his jail time now.

Such arrests occur at alarming rates; some families even have multiple members incarcerated, and facilities, which can hold thousands of inmates at a time, are overflowing. Since September, Chinese officials have been funneling prisoners out of the area, likely sending them to different provinces. Nearly 300,000 people have been transferred to Gansu province and northeastern China alone.

According to testimonies of those held in the camps, some of the centers are disguised as ordinary buildings, but they are guarded by armed men. The detained Uyghurs and Kazakhs have to sing every day. If the guards do not find their singing satisfactory, they will not be given food.

One former inmate said, “We often heard screams. We were also beaten, but it is more frightening to hear such horrible screams. Everyone dares not to say anything, only look at one another in silence.”

“People are beaten every day,” a prisoner said. “The guards on duty will pick one or two people to be beaten. The screams are unbearable. Those guards have no purpose other than just to have fun.”

The harsh treatment enacted against ethnic minority residents in Xinjiang has raised serious concern from the United States, Germany, France, and policymakers from around the globe. They called on China to close the camps immediately.

ChinaAid exposes abuses, such as those suffered by people in Xinjiang, in order to stand in solidarity with the persecuted and promote religious freedom, human rights, and rule of law.

ChinaAid Media Team

Cell: +1 (432) 553-1080 | Office: +1 (432) 689-6985 | Other: +1 (888) 889-7757

Email: [email protected]

For more information, click here